So, naturalists observe, a flea

Has smaller fleas that on him prey;

And these have smaller still to bite 'em, And so proceed ad infinitum.

Jonathan Swift, extract from On Poetry: A Rhapsody (1733)

The popular notion that stories about people changing size are aimed at children is an odd one when you look at it with an adult eye. I find it impossible, for example, to think of the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, pinned to the ground by a thousand tiny arrows, without also recalling that the author Jonathan Swift is said to have had Meniere’s Disease – a kind of vertigo which can lead to collapses, as if suddenly defeated by the smallest of everyday things. In this way, a rapid change of scale can be seen as a metaphor for something that brings us ‘down to size’, such as an embarrassing heath condition, a change in social status, or a shift in perspective.

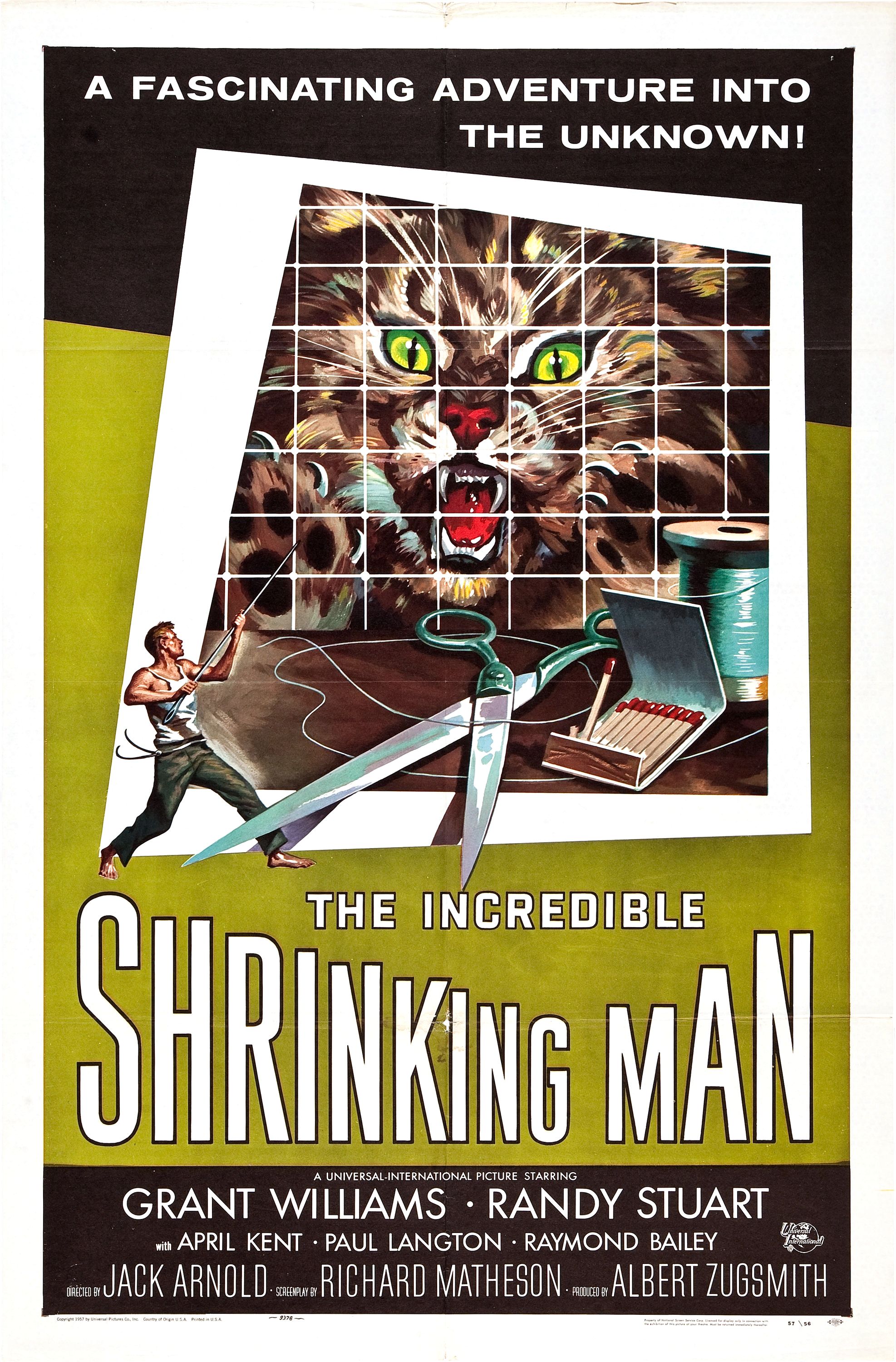

The popular notion that stories about people changing size are aimed at children is an odd one when you look at it with an adult eye. I find it impossible, for example, to think of the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, pinned to the ground by a thousand tiny arrows, without also recalling that the author Jonathan Swift is said to have had Meniere’s Disease – a kind of vertigo which can lead to collapses, as if suddenly defeated by the smallest of everyday things. In this way, a rapid change of scale can be seen as a metaphor for something that brings us ‘down to size’, such as an embarrassing heath condition, a change in social status, or a shift in perspective.  The idea of being humbled by one’s own scale assumes almost existential proportions in Jack Arnold’s 1957 film, The Incredible ShrinkingMan. Coming to terms with the slow disappearance of every area of his life in parallel with his size, the protagonist has a series of encounters with scaled up domestic dangers culminating in a (relatively) epic battle with a house spider which forces him to confront the prospect of a life characterised by a constant fear of death. In an extraordinary sequence featuring imagery of galaxies seen from space he gives voice to a growing realisation of his own hubris and a mystical revelation that there is nothing so small as to be insignificant to the Deity.

The idea of being humbled by one’s own scale assumes almost existential proportions in Jack Arnold’s 1957 film, The Incredible ShrinkingMan. Coming to terms with the slow disappearance of every area of his life in parallel with his size, the protagonist has a series of encounters with scaled up domestic dangers culminating in a (relatively) epic battle with a house spider which forces him to confront the prospect of a life characterised by a constant fear of death. In an extraordinary sequence featuring imagery of galaxies seen from space he gives voice to a growing realisation of his own hubris and a mystical revelation that there is nothing so small as to be insignificant to the Deity.-o-

Alexander Payne’s 2017 wry science fiction drama Downsizing concerns the discovery of a revolutionary biological procedure which shrinks living organisms to less than 1% of their original size. Unlike Gulliver and the Shrinking Man, the novelty here is that people are actively choosing to take part in this experiment. The discovery, originally hailed as a solution to overpopulation and global waste production, rapidly finds its way out of the lab into the hands of commercial corporations who are keen to promote it as the ultimate lifestyle choice.

Matt Damon plays Paul, an occupational therapist who is beguiled by the idea of being ‘made small’ in order to live like a millionaire without the guilt, and at a fraction of the cost, in a miniature real estate leisure park. The first part of the film has a lot of fun exploring the practical implications of such a wide scale social revolution alongside the emotional consequences. When Paul and his wife say goodbye to their friends and place their wedding rings in a customised keepsake box in preparation for undergoing ‘the procedure’, it’s almost like witnessing a kind of death. Later, waking up in a post miniaturisation recovery ward, Paul discovers too late that his wife refused to go through with her own miniaturisation at the last minute and that he has been condemned to live his dream life in a luxury doll’s house community alone. The arrival of his now supersized wedding ring in a van carried by two scaled down delivery men serves to underline the comic poignancy of his situation.

That’s only the first of his disappointments though. It's in the nature of fictional utopias, however small, that their glossy facades hide moral flaws and hierarchies every bit as corrupt as those they were built to replace. In this case, the true cost of his luxury lifestyle becomes clear when Paul recognizes his neighbour's cleaner from the TV news as a Vietnamese dissident, 'made small' and trafficked against her will. When he accompanies her back to her accommodation on a bus that passes through the perimeter wall of the luxury development like a mouse entering a hole in the skirting board, the scene opens out to reveal a vast miniature slum, peopled by scaled-down refugees. He is horrified to discover that many of them risked death to get there in search of a better standard of living yet still have no decent health care or job prospects.

As the story progresses, Paul is torn between the very real and necessary work that he could be doing in the slums, and the appeal of joining yet another experimental community that he hopes might just save the planet and give his life the meaning he yearns for.

That’s only the first of his disappointments though. It's in the nature of fictional utopias, however small, that their glossy facades hide moral flaws and hierarchies every bit as corrupt as those they were built to replace. In this case, the true cost of his luxury lifestyle becomes clear when Paul recognizes his neighbour's cleaner from the TV news as a Vietnamese dissident, 'made small' and trafficked against her will. When he accompanies her back to her accommodation on a bus that passes through the perimeter wall of the luxury development like a mouse entering a hole in the skirting board, the scene opens out to reveal a vast miniature slum, peopled by scaled-down refugees. He is horrified to discover that many of them risked death to get there in search of a better standard of living yet still have no decent health care or job prospects.

As the story progresses, Paul is torn between the very real and necessary work that he could be doing in the slums, and the appeal of joining yet another experimental community that he hopes might just save the planet and give his life the meaning he yearns for.

-o-

This is not a film that is content with simply putting consumerism under the microscope and leaving it at that. Its wide-ranging and unforgiving lens also takes in the idealism of alternative communities, the hero worship of iconoclastic thinkers and the corrosive way that the desire to make a 'big' statement with one's life can distance us from what's most obvious and important.

Don't be put off or wrong-footed by the feel-good vibe of some of the trailers – you need to be prepared for some hard reflection, a completely gratuitous drug taking scene and an extended sequence of uncomfortable but deeply felt swearing. While it’s entirely possible that the director wants to deliver a shock to our complacency, I genuinely don't believe he sets out to be casually offensive. Beneath its whimsical premise, this is actually a very passionate and serious film. My best guess is that its message, similar to that of the Incredible Shrinking Man except with a different emphasis, is that no one’s life is too small to be insignificant.

I think it just wants to be absolutely certain that no one thinks it’s trying to simplify the complex issues it features for the sake of talking down to the children.

This article was originally published in Radius Performing magazine, Summer 2018

No comments:

Post a Comment